CDHPs Need...Consumers

- Rob LaHayne

- Mar 8, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 15, 2019

Last week I bought diapers for my daughter on Amazon. For earlier generations, I imagine this type of transaction went something like this:

Step 1: Determine diaper supply is low Step 2: Go to a grocery store or a pharmacy Step 3: Find diapers that are either on sale or that worked last time Step 4: Purchase the diapers Step 5: Repeat next time you’re low on diapers

My experience, however, was drastically different. I spent at least two hours researching online the various different diaper options available. First, I scanned through thousands of reviews from other users. Then I carefully read the ingredients made to use the diapers - are they organic? Are they biodegradable? Do they contain plastic? How likely are they to cause a diaper rash? Which are the most absorbent?

Next, I joined a Facebook group for new parents and read through diaper forums. After I was able to narrow it down to a couple of options, I turned to my personal community; friends and family who also have babies.

Another few hours of texting, and I am convinced that I have found the best diapers for my daughter and the environment at the lowest possible price. In all, I probably spent 4-6 hours of time. As my parents read this, they probably think I’m crazy, but my daughter deserves the best, and I refuse to be overcharged. Plus, that’s just the way things are done in the age of consumerism so none of this process felt like overkill; even if only for a $12 pack of diapers. And I don’t think I’m any different than most American consumers. These days this methodology can be applied to just about any shopping experience no matter how big or small - except healthcare.

Consumerism in Healthcare

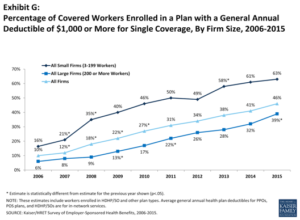

In the early 2000’s, an important shift in healthcare started to occur that would have led you to believe that in 2017, people would be interacting with the health care system in the same way that I shop for diapers with the introduction of Consumer Driven Health Plans (CDHP’s aka High Deductible Health Plans or HDHP’s). In order to address the rising cost of health insurance, employers started shifting the cost burden onto members. Insurance premiums went down, but members now had to pay for much more of the services before insurance kicked in. New tax-advantaged health savings accounts were introduced to help members afford the medical services that would now have to be paid out of pocket. The theory was that this would have a ripple effect in the way that we interact with the system. Since members would have more skin in the game, they would become better consumers and proactively shop for services; demanding the best prices from the best providers.

It would also cut down on wasteful spending for unnecessary services and even potentially reduce unnecessary emergency room use. In turn, health systems would meet consumers with fairer prices and the whole system would be fixed! By 2005 about 5% of all members were enrolled in a CDHP.

Unfortunately, despite that number ballooning to 30% in 2017, the ripple effect still hasn’t happened. Members have not learned to become consumers - and it's a problem for providers, employers, and members alike.

According to a recent study by Journal of the American Medical (JAMA), consumerism behavior of those enrolled in CDHP’s is alarmingly low. Their study found that despite increased cost burdens, only 14% of members compared prices; only 14% compared quality of service providers, and only 6% negotiated prices! To take it further, JAMA then asked the few consumers out there what their results were ad 52% of actually reported paying less for their services.

Translation: over 50% of the time that members took a similar approach to their medical care as I did with diapers, they saved money! And given the cost of medical care in this country, it’s safe to assume it was thousands of dollars more than I saved on diapers.

Additionally, the American Journal of Medical Care recently published a study that indicated that CDHP’s may have had very little impact on the overall spending behaviors of consumers, and specifically have done very little to reduce unnecessary spending (i.e. tests and procedures that have no clinical benefit to patients, but still expose them to risk and expense).

Roughly $750 billion is spent on wasteful and unnecessary healthcare annually according to the National Academy of Sciences.

This further highlights the problem of a lack of consumer-ing by members. If we now have more skin in the game than ever before with regards to our health care costs, why aren’t we challenging anybody on price, quality, or justification for the services and procedures that we’re spending thousands of dollars for?

The Good News

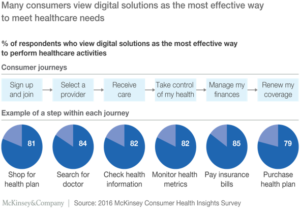

Despite the very complicated system that is our reality, there are tools that can help. More and more digital tools become available every day to help guide members and shift the power dynamics of health care.

CDHP’s are clearly not enough to change behavior and lower costs. It will take a more educated, empowered consumer base. It’s on the collective “us” as members of this healthcare system to take control, leverage the tools available to us, and create #realreform.

Comments